Most golfers who look for swing tips are serious about the game. They really want to get better, so they practice and watch videos. Many of them are frustrated not because they aren't trying hard enough or aren't following the rules, but because the results never seem to last. A tip might work for a session or two, or even a round, but then the old miss comes back. That cycle makes golfers think they are doing something wrong, when in fact the advice is usually the problem.

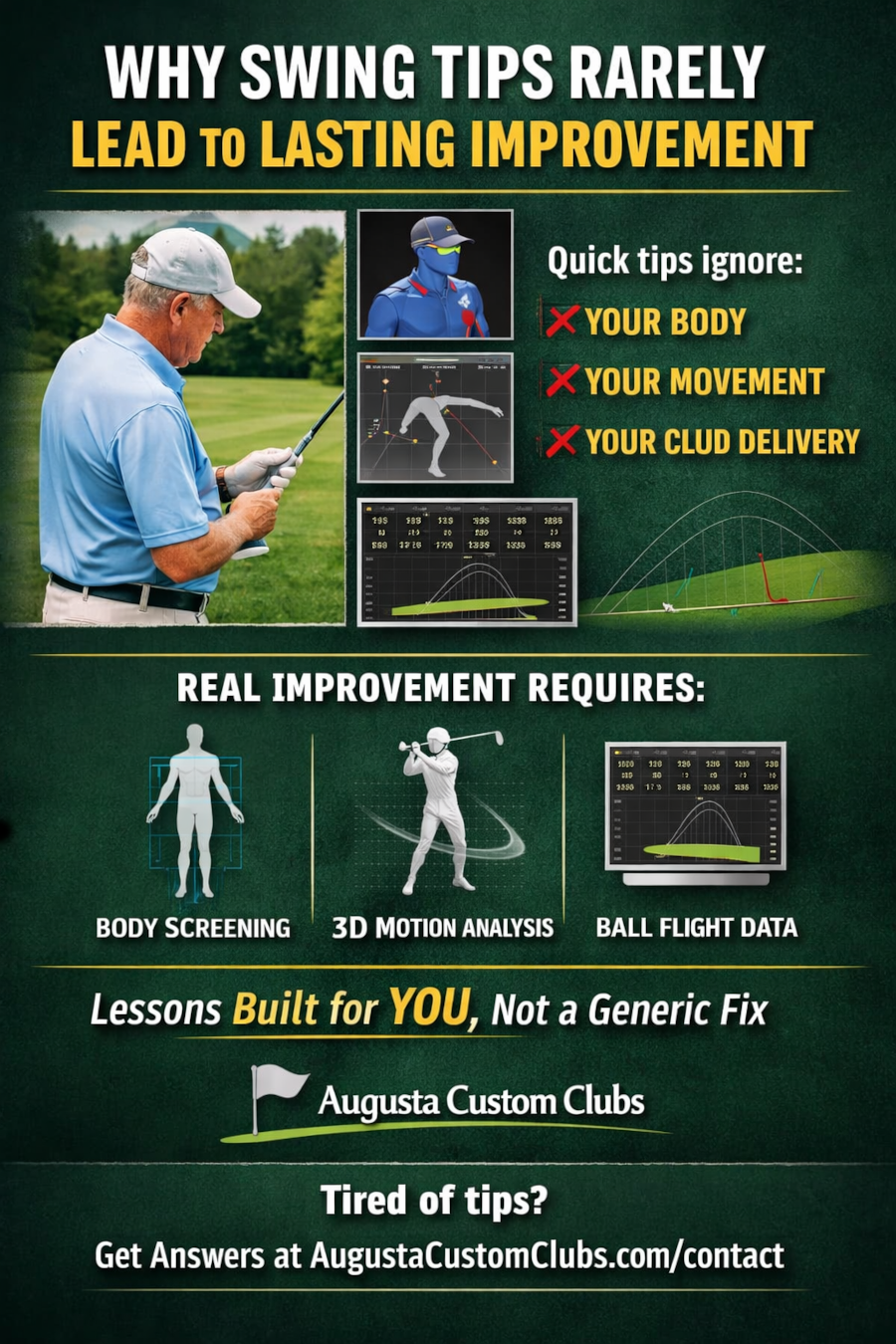

Swing tips usually don't work because they treat the golf swing as a series of positions rather than a moving system the body controls. Most tips assume that any golfer can just "do" a movement on command, without considering how they are built, how they move, or their physical limits. When a tip doesn't account for how the body really moves, it tells the golfer to rely solely on willpower to break old habits. That way of doing things doesn't work very often.

To make lasting progress, you need to understand how the golfer's body, their movement patterns, and their ball-striking are connected. The swing is not something that happens outside of the body; it is a part of the body. The way the hips turn, the way the torso moves, the way the arms respond, and the way the club is finally presented at impact are all connected. When teaching doesn't take those connections into account, it only makes things worse by making things confusing.

The main idea is simple but often missed: long-term improvement doesn't come from getting better tips; it comes from knowing how your swing works. When body function, movement patterns, and club delivery are all looked at together, the golfer can understand the changes; they work with what their body can do, and they hold up under pressure and time. That's the difference between a tip that goes away and an improvement that stays.

Most golfers have a very clear idea of what they want from a swing tip: that one thought or change can change years of bad movement patterns. The promise of simplicity is what makes a tip appealing. One thought, one feeling, one change that is meant to change the whole swing. That expectation makes sense, especially in a sport where it's hard to get better and there's little time, but it's also unrealistic.

Many swing tips assume that all golfers can move the same way. They say that a golfer can rotate more, shallow the club, or "use the ground" if they just try hard enough, no matter how strong, mobile, or balanced they are. In reality, golfers have very different physical abilities when they swing. Hip rotation, thoracic mobility, lead-side stability, and motor control differ significantly among players. Even if both golfers are very motivated, a tip that works for one may not work for the other.

This is where general advice starts to fall apart. Swing tips are meant to be useful for a wide range of people, so they can't account for everyone's individual requirements. If a tip doesn't match what a golfer's body can actually do, the golfer either doesn't do it right or makes up for it in some other way. The basic movement pattern stays the same in both cases. The difference between general advice and customized movement ability is very important. For lasting change, the golfer's body needs to be able to support the changes, and sometimes even more than it can already.

Even with these problems, swing tips often seem to work in the short term. A new tip gives the golfer an exaggerated feel that throws off their usual timing or sequencing. That disruption can change the way the ball flies almost right away on the range, where the conditions are controlled, and the consequences are small. The golfer thinks the tip is working when they see a straighter shot or a higher launch.

But what usually happens is not real improvement but compensation. The exaggerated feel changes one part of the motion for a short time, and the rest of the swing adjusts just enough to make it work better. Those adaptations can work in the moment, especially when the golfer is focused and swinging slowly. They make it seem like progress is being made, but they don't change the reason for the miss.

It's easy to mix up short-term changes in ball flight with long-term improvements when you don't get objective feedback. Success on the range can mask the fact that the original movement pattern is still there and will resurface when you are under pressure, tired, or going faster. When the tip stops working, the golfer usually looks for the next one rather than realizing the tip itself is the problem. This cycle shows why tips seem helpful at first but don't usually lead to lasting change.

The TPI method emphasizes that the body limits the golf swing, a basic rule of good teaching. The swing is not separate from the golfer's physical abilities; it is shaped by them. Mobility, stability, and motor control all affect how much a golfer can rotate, how they load into the ground, how they move in a sequence, and how often they can repeat those movements. When instruction doesn't take those limits into account, it asks the golfer to do things their body may not be ready for.

A golfer's ability to turn or separate parts of their body efficiently can be limited by mobility issues. If you have stability problems, it can be hard to control your posture or move forcefully without compensating. Lack of motor control can cause swings that depend on precise timing and sequencing. These things aren't problems with your character or your efforts; they're just things that happen. A swing tip that assumes free rotation or perfect coordination might work for a golfer whose body can handle those demands, but it might not work for someone else.

This is why a tip that works for one golfer may not be effective for someone else or even make things worse. If a player can't move their hips, they might try to turn more by forcing their lower back to rotate. A golfer who doesn't have good stability on the lead side might try to shift the pressure too quickly, losing their balance or posture. In both cases, the tip doesn't work because the golfer didn't try hard enough; it works because the golfer didn't pay attention to the body-swing relationship.

This connection changes how people think about improving things. The more important question is not whether a tip is good or bad in general, but whether it fits the golfer's physical profile and movement abilities. The swing gets better, more repeatable, and much less likely to break down under pressure when the instruction matches what the body can do and, when necessary, works to improve those abilities.

One of the most misleading aspects of golf lessons is the idea that a given ball flight always has a single cause. Two golfers can hit the same slice, hook, or pull using very different ways of moving. The shots look the same from the outside. They are not always so, though, when you look at them from a cause-and-effect point of view.

A slice is a good example. A golfer might slice because the clubface is always open compared to the path. Another person may slice because their path is too out-to-in, even though the face is mostly neutral. A third may have a good face and path combination, but they may not hit the ball well and struggle to control the low point. Most "fix the slice" tips address only one of these situations, but they assume they apply to all of them. For the golfer whose problem is different, the tip either doesn't work or makes things worse.

This is where diagnosis based on appearance fails. When instructors and golfers focus only on the swing from one angle or on what "looks right," they tend to focus on symptoms rather than causes. The flight of the ball shows what happened when it hit the ground, but it doesn't explain why. If you don't know the movement patterns that caused that impact condition, teaching becomes guesswork.

Three-dimensional motion analysis makes things clearer than just watching them. It shows the real order and connections that lead to a certain ball flight by measuring how the pelvis, torso, arms, and club move through space and time. It tells you if a golfer's problem is with how they load and rotate, how they transition, or how they hit the ball with the club. Instead of giving a general fix based on the shape of the shot, instruction can focus on the real problem with the golfer's movement pattern.

When you find the real reason for a miss, it's easier and more reliable to make improvements. Instead of trying to follow a tip meant for someone else's swing, the golfer focuses on the one thing that makes their ball fly. This change, from matching tips to shot shapes to matching solutions to causes, is necessary for long-term progress.

Standard video and mirror-based feedback can be helpful, but they don't work well on their own. A video shows how the swing looks from a certain angle, and mirrors help you remember key points or positions. What they don't always show is how the body moves to get into those positions. Because of this, golfers often focus on how things look instead of how they move.

Visual feedback often focuses on static positions during a changing movement. A swing can look good at the top or when it hits the ball, but it could still be based on bad sequencing or compensations. Pelvic rotation may seem fine, but it might happen too late. The torso can turn, but not in the right way with the pelvis. The lead arm may look like it's on plane, but its movement pattern makes the timing of the hand action through impact important. It's hard, and sometimes impossible, to see these details consistently with just the naked eye or standard video.

Teaching based on feelings adds another level of uncertainty. What a golfer feels during the swing is not always what is really going on. Past habits, compensations, and perceptions all affect how we feel. A golfer might think they are making a big change, but objective measurements show that the change is small or nonexistent. On the other hand, a small improvement that can be measured may feel completely wrong to the golfer. When feeling is the main guide, progress is hard to make and hard to repeat.

To make lasting changes, you need to be clear about what needs to change and why. Pelvic rotation rates, thorax sequencing, and lead-arm behavior are all examples of measurable movement patterns that clarify things. They link what we see and what we do to objective cause-and-effect. When a golfer knows not only what their swing looks like but also how their body is moving and how that affects their ball flight, they can give better instructions. The golfer doesn't just guess or copy what others do; instead, he or she works toward valuable, repeatable, lasting changes.

When swing tips are used without a diagnosis, they don't often change an existing movement pattern. They are more often put on top of it. A golfer changes how they feel or where they stand, but the problem that caused them to change stays the same. The rest of the swing changes just enough to make the new idea work. This process makes things better instead of fixing them.

These payments start to add up over time. To fix a mistake, you add one tip; to fix what the first tip messed up, you add another; and to get back to a sense of balance or timing, you add a third. The swing needs increasingly precise sequencing and awareness to stay together. The golfer can make good shots as long as everything is in the right place. When timing goes off by even a little bit, performance falls apart.

The main reason for this problem is the lack of a diagnosis or objective measurement. There is no way to know if a tip is fixing the problem or just hiding it if you don't know what is actually causing the ball flight. There is no way to tell if a change is fundamental or compensatory without measuring it. The golfer has to rely on how they feel and short-term results to show that they are making progress.

Compensation is weak by nature. They need the right conditions to do well. When the focus shifts from mechanics to the target under pressure, compensations tend to fail. When you're tired, it's harder to keep them in good condition. Faster speeds make their weaknesses worse. This is why swings built on tips often work on the range but not on the course, and why improvements based on pay don't last long. Durable improvements come from eliminating the need to pay for fixes in the first place, not from keeping track of a long list of fixes.

To make lasting progress, you need to know more about the golfer than just their swing. To make lasting changes, you need a clear idea of how the golfer's body moves, what it can and can't do well, and how those physical traits affect the delivery of the club. Without that base, teaching becomes a matter of guesswork rather than facts.

The first step is a physical screen. The swing must work within the limits set by mobility, stability, and basic movement ability. These things affect how a golfer can rotate, load, and maintain their posture without compensating. If you don't listen to them, you might get advice that sounds good in theory but isn't practical for that person.

Movement assessment builds on this by looking at how the golfer actually moves their body during the swing. It finds patterns in the order of movements, how pressure moves from one part of the body to another, and how different parts of the body work together. This test goes beyond looks and feel to show how motion is organized over time instead of where the club is at any given time.

Objective swing data is the link that connects movement to results. Quantifiable data regarding rotation rates, sequencing, and club delivery elucidate causation. It lets you judge changes by whether they fix the real cause of a miss, rather than just how they look or feel. This objectivity replaces guesswork with being responsible.

Targeted drills finish the job. These drills are chosen not to force everyone to do the same thing, but to help the golfer find movement patterns that work for their body and goals. They are specific, purposeful, and progressive, reinforcing changes that are both possible and useful. Every drill has a specific purpose in a bigger plan.

When improvement follows this structure, it is planned and not random. We don't just assume progress; we measure it. Changes are made based on facts, not frustration. The swing gets better at doing its job, can be done more than once, and lasts longer. This is the difference between quick fixes and real progress that lasts.

An effective lesson starts by giving you facts instead of making assumptions. The process doesn't start with a tip or a preferred model; it starts with getting to know the golfer as a person. Body screening based on TPI principles shows the golfer how they can move, where they can't, and which movement patterns are likely to persist. This step alone eliminates much of the general advice that would be wrong or unhelpful.

Then, three-dimensional motion capture gives a clear picture of how the golfer's body and club move during the swing. It shows sequencing, rotation rates, and segment relationships that can't be reliably seen or felt. Instead of guessing why a certain ball flight happens, the lesson shows the exact movement pattern that causes it. This changes the focus of instruction from opinion to cause and effect.

The data on ball flight closes the diagnostic loop. The movement patterns measured are directly linked to outcomes that can be measured at impact. Face angle, path, contact point, and launch conditions show if a change is fixing the real problem or just making the swing look different. The ball's movement, not how closely the swing matches a mental picture, is how progress is measured.

Then, the lessons are tailored to the golfer's physical abilities and swing goals. Drills and changes are chosen because they work for the golfer's body and goals, not because they are the best position or a popular saying. The goal is not to make every swing look the same, but to make each swing work better, be easier to repeat, and be more in line with what the golfer wants. Changes can last over time because of this personalized approach.

Swing tips don't usually help you get better in the long term because they are meant to work for everyone, but golf swings are not. They promise easy answers to hard, personal problems and rely on how things feel and look rather than on diagnosis and measurement. Because of this, they only make temporary changes and compensations, resulting in frustration rather than lasting progress.

To make lasting progress, you need to stop focusing on gathering ideas and start focusing on solving problems. When you understand how a golfer's body, movement patterns, and club delivery work together, you can give them clear and useful instructions. Changes make sense, fit the golfer's body, and can handle stress and time.

The difference is not in the amount of work or drive those have always been there. It's all about the approach. To turn short-term fixes into real, lasting improvements, you need to stop looking for tips and start solving problems.